Footprints: Deaths raise spectre of dope

Matloob Haider, an aspiring bodybuilder, didn’t betray any sign of strain when he returned home late last Tuesday night. As he was prepping for the Gujranwala bodybuilding championship

Matloob Haider, an aspiring bodybuilder, didn’t betray any sign of strain when he returned home late last Tuesday night. As he was prepping for the Gujranwala bodybuilding championship, he had started to spend more time at the gym. After all, it was the first contest the 22-year-old had ever planned to take part in; he wanted to win.

“He ate his dinner and sat here chatting with me. All of a sudden, he started complaining of suffocation in his chest and asked me to take him to a doctor,” says his ageing mother at their home in Rahwali, a small town a few minutes’ drive from Gujranwala.

She rushed him to a nearby clinic and was advised to immediately shift the youngest of her five sons to a bigger hospital in Gujranwala. “We were calling Rescue 1122 to arrange an ambulance when Matloob collapsed and stopped breathing,” she continues, her eyes wet.

Matloob had started training at a nearby gym at the age of 13 and was soon employed as a trainer there. Though he had never participated in a bodybuilding championship, the boys he helped train have won medals in several competitions.

“He was crazy about this sport,” says his elder brother Mehboob Ahmed, a welder by profession. “But God took him away only two days before the contest.”

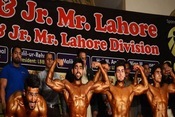

Matloob was the fourth bodybuilder to die within the short span of two and a half weeks between April 2 and 19. Like him, two others — Hamid Ali aka Ustad Gujju from Sialkot and Rizwan Ahmed from Gujranwala — were reported to have suffered sudden heart attacks. The fourth, Hamayoun Khurram, who was from Lahore and a gold medallist in the recent South Asian Bodybuilding Championship, is claimed by his family to have died after his trachea tore whilst eating.

No investigation has been carried out, but media reports blame widespread and unsupervised use of performance-enhancing drugs, growth hormones and steroids.

“I cannot say whether my brother used steroids or any other drugs,” says Mehboob. “But I also cannot say he didn’t. It was his field and he knew better. What I know is that he had never had any health problems.”

In Sialkot, Rizwan Ali, younger brother of Ustad Gujju who won the bronze medal in the Pakistan Bodybuilding Championship only two days before his death on April 2, insists that his brother didn’t use any kind of food supplements or drugs. “My brother died of a heart attack. I don’t know why the TV channels are insisting that he used to take steroids,” he says, conceding though that the 41-year-old bodybuilder had some time ago developed liver and stomach problems, a common outcome of the frequent use of muscle-building substances.

Shahzad Akhtar, an information technology student at the University of Sargodha who used to work out with Matloob, is not sure whether his trainer took food supplements, but contends that most struggling bodybuilders frequently take such substances.

“These drugs and supplements are freely available at stores everywhere and commonly used by athletes,” he explains. “Some stores even specialise in substances used for bodybuilding. The gym trainers and management often encourage athletes to use food supplements to improve their physique and win contests.”

Some gym operators concede that the “abuse” of food supplements by bodybuilders is on the increase. “There are reasons for this rapid increase in the use of such substances. Bodybuilding is not just a sport; it is a lifestyle that not everyone can afford,” explains a gym manager in Johar Town, Lahore, on the condition of anonymity.

“Since most aspiring bodybuilders come from lower middle-class families and cannot afford the kind of diet required to build muscles and sculpt their bodies, they start taking food supplements and using performance-enhancing drugs,” he says. “Budding bodybuilders would do anything to make a name.”

According to him, the abuse of endurance drugs and food supplements isn’t restricted to Pakistan. “It is common amongst bodybuilders everywhere and so are the deaths of athletes on account of this abuse. The best way of controlling the abuse of such substances is to regulate their import and sale and educate athletes about the risks.”

The president of one of the two factions of the Pakistan Bodybuilding Federation (PBF), Shaikh Farooq Iqbal, is reluctant to acknowledge a direct link between dope and the deaths of the athletes. “We don’t have any evidence to suggest the link except speculation. But we are taking action with the help of the government to check the abuse of food supplements and endurance drugs,” he argues.

The PBF has cancelled the registration of all fitness clubs and gyms and asked them to provide affidavits that they do not encourage the use of dope. “Those failing to do so may face closure,” he adds.

Admitting the presence of a culture in most gymnasiums and clubs of using prohibited steroids and drugs, he says the menace can be controlled only by regulating the food supplements market and setting up a dope-testing laboratory. “Dope tests are expensive to get done from abroad, costing up to Rs50,000,” he says. “We cannot afford these tests for local competitions unless we have a laboratory in the country.”

Indeed, the sudden deaths have caused fear among bodybuilding enthusiasts. “Gym users are now worried about whether these deaths were directly or indirectly related to the abuse of steroids,” Akhtar, the IT student, says. “But will this discourage them? I doubt it.”

(Source: Dawn News)

(Source: Dawn News)